‘Each woman can create 10 jobs. One mn = 10 mn jobs’

Nita Kejriwal: On an average, one cluster-level federation has 30 village organisations, 450 self-help groups (SHGs) and 5,000 members. It is aimed at building capacity, hand-holding and self-help. We are trying to develop 1,500 model cluster federations so that they become immersion sites for other cluster-level federations. These are already conducting financial intermediation as they get Community Investment Funds. Some mature federations have crores of rupees in their corpus fund, which they use to give loans to their members. That work will go on but the liaison with banks and credit support for other financial services will also be conducted parallelly. These federations help in livelihood planning for each member, support Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs), negotiate with the market, help members access the entitlements that come from different government departments and have MoUs with Amazon and other such e-commerce retailers. An important job of these federations is to bring forth the demands of the members at different forums such as Gram Development Plans and influence policy-making. These federations have started Gender Justice Centres too.

On women-led cooperative banks and financial inclusion

Chetna Sinha: The women who came together to form the Mann Deshi Sahakari Bank said that we do not know to read and write but we can count. And I think that was a powerful statement. They meant that women at the grassroots level know financial planning and how to support each other. Now women vendors come together and pledge the group’s guarantee in repaying the loan. They are even moving to individual entrepreneurship. We are looking at impacting one million women entrepreneurs, each of whom will create 10 jobs. That means one million women entrepreneurs with 10 million jobs. This is the potential you have at the grassroots level.

Anjini Kochar: In terms of financial inclusion, India was at the bottom since 2012. Those numbers have improved tremendously. So even in a state like Bihar, the percentage of women who report having access to a savings account is 70 to 80 per cent. I would have to say that NRLM and self-help groups have played a large role in this. It hasn’t just been the Jan Dhan accounts. SHGs have pushed women to open their own accounts. Now we need to see how financial access translates into growth. We see huge heterogeneity across the world in this respect. For example in Bihar, we were looking at the Indira Gandhi Matritva Sahyog Yojana (IGMSY), the maternity support programme, which gives credit payments directly to women’s savings accounts. The Rs 2,000 coming to the woman’s account was being withdrawn immediately by the men in the household. This is an extreme example but it shows you what has to be done so that benefits are real.

On women in urban slums influencing policy-making

Bijal Brahmbhatt: The Mahila Housing Trust’s mission was to improve the housing, living and working environment of poor women in the informal sector by directly empowering them and giving them the technical know-how to be able to talk and negotiate with the government and private sector on an equal basis. In Ahmedabad, women needed access to water connection or sanitation. We opted for network solutions to reduce inequality.

A woman represented each household and then each elected community action groups, which were specifically trained in understanding the governance systems in cities. It began from there and expanded to include access to legal electricity, housing finance and legal land rights.

In urban areas, climate change is something which intersects directly with the kind of built environment that you create. Our communication was very smartly designed to make them understand the complexities of climate change. And the idea was to demystify scientific facts so that they could co-create solutions. The second aspect was to engage technologists and scientists with these poor women to propagate technologies that would help them adapt or mitigate the impact. They took these ideas to the city governments and supported the development of heat action plans or cool roof policies or monsoon action plans at that level. Today, 125,000 families, an average of five persons in each family, have joined this movement against climate change.

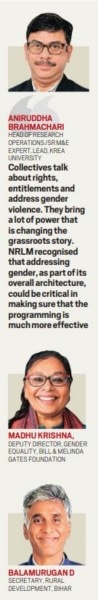

Madhu Krishna: Our latest evaluation of NRLM shows that you can increase incomes by 19 per cent. There was a decline in share of informal loans by 20 per cent and an increase in household savings. When you’re talking about resources, if you can show the power that women can display, both the technical skills they bring to the table and the local knowledge and context they bring, that’s super helpful. In Odisha, the running of fecal sludge treatment plants (FSTPs) was entrusted to SHGs. That kind of initiative is now diffusing across other States. Schemes like MNREGA build productive assets, not only for cities but also for individual women. This convergence is actually going to be the next big game changer.

On including the ultra poor in collectives

Balamurugan D: The World-Bank funded Jeevika is able to access more than Rs 21,000 crore of credit linkage from banks, helping women come out of poverty. Though the ultra-poor become part of an SHG, they can’t even afford five rupees of savings per week. Bihar’s Satat Jeevikoparjan Yojana (SJY) is a sustainable annual programme to select ultra-poor families and work with them. The best part is that it is being done by the SHG itself, the village organisations (VOs), which select the poorest of the poor. When you make selections through these community-based organisations, particularly VOs, the inclusion and exclusion error is very minimal. The most important element here is coaching and household visits. Initially, Rs 10,000 is given as a grant to start some activity and we also give Rs 7,000 in support money for the initial seven months. We have 1,44,000 families right now under this programme more than 50 per cent of whom moved from one ladder to another. They’ve started saving Rs 250 per month.

On the socio-economic impact of the Meghalaya model

Hasina Kharbhih: It is a model that has scaled very deeply in the seven states of the Northeast and in neighbouring countries of Bangladesh, Myanmar and Nepal. The lack of employment, an entrepreneurial support system and market resilience meant that women from indigenous communities with traditional skills had lost value. Vulnerable, they became migrants and exposed themselves to the risk of human trafficking. Now we encourage them to revive traditional crafts and expertise and help them market their products. The biggest enabler has been the work-from-home flexibility. Our business model involves a centralised raw material distribution for quality control, engaging storytelling of the pattern and motif in their creations and the uniqueness of the product that is sustainable in nature. This has decreased migration and human trafficking over the last 14 years. Each woman is earning almost Rs 7,000 to 8,000 a month. It is a gender-enabler because the husband distributes the raw material while the woman weaves.

Newsletter | Click to get the day’s best explainers in your inbox

On private funding and scaling for women-led cooperative businesses

Chetna Sinha: Even if women are a part of the SHG, when you want to start a business, you need capital. One is the capital or loan you get from the bank but women do not have collateral. That’s where Mann Deshi back comes in. Many wealthy women want to support other women, so there’s a sort of grant equity. Women are using apps like Mera Khata and Mera Bill for their financial management and making very simple entries of their business. At our bank, women get a revolving grant to buy the machinery. Private investment can come in the form of hypothecated machinery. And when private investment comes, your standardisation and financial planning follow, which help women to graduate from proprietorship businesses to LLPs, or private limited companies.

Madhu Krishna: We are helping NRLM create a very strong digital architecture. So, while the current MIS systems rarely look at the SHG credit linkages, once we have a strong database, and the credit histories of individual women entrepreneurs, we think this will be a very big thing. Then you can bring in multiple cluster-level federations and provide them with some sort of an enterprise support system. But definitely, scale is important.

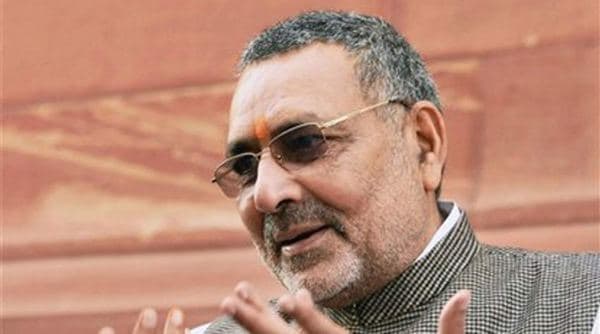

Giriraj Singh, Minister of Rural Development and Panchayati Raj

Giriraj Singh, Minister of Rural Development and Panchayati Raj

. (File)

Giriraj Singh, Minister of Rural Development and Panchayati Raj

My mission is to ensure that no rural woman, who wants to connect with the National Rural Livelihood Mission (NRLM) is left behind. I will also improve the turnover of 5.9 lakh crore women. If half of the country’s population improves

its earnings, the women will be significant contributors to the national GDP. Today, 8.35 crore women are connected to

NRLM and there are 5.9 lakh crore bank linkages, while the NPAs have reduced to 2.5 per cent