Death in a resort

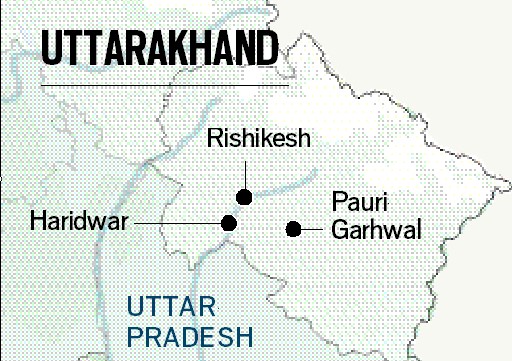

A DEATHLY calm shrouds the ghostly white building that’s surrounded by champa and pine trees. It’s a far cry from the “tranquil surroundings” advertised in glossy pamphlets and on the website of Vanantara Resorts in Rishikesh, over 50 kilometres from Dehradun.

The Uttarakhand resort is now at the centre of a sensational murder that hit the headlines a couple of weeks ago while casting a light on how business, politics and ambition can cross paths, sometimes to dangerous consequences.

On the night of September 18, Ankita Bhandari, a 19-year-old receptionist at Vanantra Resort was killed allegedly by three persons, including her employer Pulkit Arya, 35, son of now expelled BJP leader Vinod Arya. Police said Pulkit had allegedly killed Ankita after she resisted his orders to provide “special services” to some of the guests at the resort.

The partially demolished resort at Rishikesh. (Express Photo by Avaneesh Mishra)

The partially demolished resort at Rishikesh. (Express Photo by Avaneesh Mishra)

With the murder resulting in massive protests across the state, the authorities swung into action — three of the accused, Pulkit and his associates Saurabh Bhaskar and Ankit Gupta, were taken into custody and the district administration demolished a section of the resort, which sparked a controversy amid allegations that it was a bid to “destroy” crucial evidence. Following Pulkit’s arrest, the Uttarakhand BJP expelled his father Vinod and elder brother Ankit from the party.

Now, weeks later, away from the cameras and hordes of media personnel who descended on this resort following news of Ankita’s death, the Chilla canal, into which Pulkit allegedly pushed Ankita, flows quietly, its gurgling waters standing witness to the events that ended in tragedy on September 18.

A family’s dream cut short

At a two-storeyed structure with moss-covered stairs leading up to the first floor, Ankita’s father Virendra Bhandari is flooded with memories of his daughter — the day she was born, the little “Goddess Lakshmi” whom he named Ankita but called “Sakshi”; the day he last saw her as he dropped her off as she left for her job at the Rishikesh resort.

Even as a little girl, Ankita, he says, was clear about what she wanted — and what she didn’t. “She told us that she does not want to live in the village. That she needs to go out and study… and study English. We knew there weren’t enough opportunities in these parts,” says Bhandari, 53, sitting on one of the stairs at the family’s ancestral home in Dobh Srikot village, in Uttarakhand’s hilly Pauri Garhwal district.

So when Ankita was around eight years old, the family moved out of this house that Bhandari’s grandparents had built and moved downhill to Pauri town. There, Bhandari enrolled Ankita and his elder son Ajay in the English-medium Bhagat Ram Modern School while he took on several odd jobs. In 2020, Ankita cleared her CBSE Class 12 exams with 89 per cent marks as a Commerce student.

“We were very proud of her. She was a good student and that is why I decided to enroll her in the English-medium school. I used to help her with her studies till Class 4, but after that, all that English got too tough for me,” he says, getting up to bring fodder for his two cows and their calves.

A narrow kuchha road, with a mountain on one side and a plunging gorge on the other, is the only access to the house that sits on a hilltop. It takes a 1.5-km trek downhill to get to a point where state transport buses ply to Pauri town.

The Haridwar home of the Aryas has been shut since the murder. (Express Photo: by Avaneesh Mishra)

The Haridwar home of the Aryas has been shut since the murder. (Express Photo: by Avaneesh Mishra)

Last year, Ankita went to live at a relative’s house in Dehradun and enrolled for a one-year certificate course at the Shri Ram Institute of Hotel Management. However, with her father losing his job as a security guard during the Covid lockdown, the family soon ran out of money and moved back to their ancestral village. Around six months into her course, with her fee arrears climbing to Rs 35,000, Ankita finally dropped out of her course and came home.

In a state whose limited job opportunities mostly revolve around the tourism industry, Ankita, like most youngsters her age, wanted to work in the hospitality sector.

So earlier this year, when Ankita’s friend Pushp (now a witness in the murder case) informed her about an opening at a resort in Rishikesh, she decided to take it up — and soon landed the job.

On August 28, father and daughter took a bus to Rishikesh. “I was asked by the resort owner to wait at the main gate of AIIMS Rishikesh. They then came in a car and took her and her small carry bag that had her belongings. They promised to keep her safe. I remember how she got into the car and waved at me. That was the last time I saw her alive,” says Bhandari, his voice breaking.

Lilawati, wife of Bhandari’s elder brother Rajendra, says that soon after Ankita left for Rishikesh, her dream job started unravelling. “Just a few weeks after she left, we sensed that she was no longer the same. Though she never really told us or her mother what was troubling her, she sounded tense and stressed,” she says.

Though Ankita was offered a monthly salary of Rs 10,000 and a room to stay at the resort, she did not live long enough to collect her first salary.

Back on the moss-covered steps, Bhandari lapses into memories of his younger child.

“Oh, there are so many things I remember about her… I was really impressed with the way she cooked. She didn’t cook very regularly, but when she did, she did it with a lot of interest. She was the one who introduced us to chowmein (noodles) and momos… Now, look at us. My mother has barely eaten anything since the funeral (on September 25),” says Bhandari. His wife and son lie listlessly in one of the rooms.

“I remember the day she was born. We were very happy that Goddess Lakshmi had finally come to our house. We already had a son and wanted a daughter… She too had a lot of aspirations, a lot of dreams because she had seen her parents struggling to put food on the table,” he says.

Power, patronage, and the Aryas

Until recently, the double-storeyed peach-and-brown building in Haridwar’s Arya Nagar locality was its most important address. The residence of now expelled BJP leader Vinod Arya, a fleet of cars parked on the road outside and party flags marked this out as a key landmark.

However, its fortunes have reversed drastically over the last fortnight. A billboard displayed prominently until a few days ago, of ‘Swadeshi Ayurveda’, an ayurveda firm owned by the Arya family, has been taken off. The big, green iron door leading to the house remains shut at all times and no outsider is allowed inside.

This strict seclusion, however, has done little to stop the town from discussing Vinod and his son Pulkit — and the murder that their famous neighbour is now linked to.

The Arya family hails from Imlikhera, a village in Roorkee that has had its share of political fame — it’s home to several heavyweight politicians, including former BJP state president Madan Kaushik and the party’s former Roorkee MLA, Suresh Chand Jain.

Sources say the Aryas were a family of modest means — Vinod’s father Munishwar Anand was a farmer and a member of the Arya Samaj. How their fortunes changed is part of a delightful lore that’s told with a lot of conviction by villagers in Imlikhera. When Vinod was a child, they say, some dacoits are said to have robbed a rich businessman and used mules owned by Munishwar to carry the loot. While the other mules went with the dacoits, one of them, loaded with gold coins, strayed from the pack and returned to its owner, Mushishwar. It is widely believed that this is how the family struck it big, purchasing land and venturing into the ayurveda business. Vinod Arya established Swadeshi Ayurved in 1995, setting up a factory that ran out the premises of their home in Arya Nagar.

With the business taking off and Vinod making a name for himself beyond Haridwar, he effortlessly transitioned into politics and soon joined the BJP.

Later, he was made chairman of the Uttarakhand Mati Board, a post that gave him the rank of minister of state in the previous Trivendra Singh Rawat-led BJP government. Vinod’s elder son Ankit too joined the BJP and was later made vice-president of the state OBC Commission.

Following the murder, both Vinod and Ankit were expelled from the party and Ankit was stripped of his OBC Commission post.

An RSS member and resident of Haridwar’s Arya Nagar, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said Vinod had serious political aspirations. “He was an RSS member. He wanted to contest elections, both to the assembly and the zila panchayat, but he never got a ticket because he didn’t have it in him to be a politician,” he says.

Another office-bearer of the RSS, someone who has been closely associated with the family, says that Vinod’s sons Ankit and Pulkit were very different from each other — while Pulkit always had a troublesome streak, his elder brother “was much more responsible”.

After his schooling at Saraswati Vidya Mandir in Haridwar, Pulkit joined Himalaya Ayurvedic Medical College in Doiwala for a diploma course. A former principal of the medical college, who didn’t want to be named, says, “I was the principal when Pulkit enrolled for the course. I used to get a lot of complaints about him, mainly about his scuffles with other students. I had asked the management to keep an eye on him.”

But in what was to leave his former classmates and teachers stunned, in 2009, Pulkit topped the Uttarakhand Pre-Medical Test (UPMT) conducted by Pantnagar University.

The high rank ensured him a seat at Patanjali Ayurveda College in Haridwar for a Bachelor of Ayurvedic Medicine and Surgery (BAMS) course. He, however, soon dropped out.

“I was in the same batch as Pulkit. He had supposedly topped the entrance exam but he rarely came to college. The few times he did, it was with his laptop on which he showed us his photographs with several politicians,” says one of Pulkit’s batchmates at Patanjali Ayurveda, adding that Pulkit was a day-scholar and used to drive his SUV to college.

Sources say Pulkit soon dropped out after he failed to meet the mandatory 75 per cent attendance to appear for the term-end exam.

Pulkit was to eventually get his BAMS degree from Rishikul Ayurvedic College in Haridwar. A senior staff member of the college says that Pulkit was in 2011 debarred from the counselling process, but later got admission in the college in 2013.

“In 2011, he tried to get into our college through UPMT. However, during counseling, it was found that the candidate’s photographs from high school and intermediate, and on the entrance form did not match. He was disqualified,” he says, adding that in 2013, Pulkit again cleared the UPMT exam and finally got into the college.

“While he was in his third year [2016], we received an anonymous letter saying several students of the last few batches had got admission through illegal methods. We started investigating and found faults with the admission process related to 31 students from four batches, including Pulkit. An FIR was registered and they were all removed from the college in September. However, after a change of government in 2017, somehow Pulkit and the other students were allowed to resume their course,” he claimed.

Uttarakhand DGP Ashok Kumar had earlier confirmed to The Indian Express that an FIR was registered against Pulkit in 2016 at Haridwar Kotwali under sections of cheating and forgery.

Razed to the ground

Outside the Vanantara Resort, policemen deployed since the murder lounge on a dust-covered sofa that has seen better days.

A significant part of the structure now stands demolished, with large, gaping holes revealing the hollowed-out insides of the once luxury resort. Most of the glass panes — which not too long ago offered a breathtaking view of the Himalayas — have been shattered and expensive furniture lie strewn on the ground outside. An ATV motorbike lies on its side, vandalised.

The security personnel aren’t letting anyone inside but that hasn’t stopped curious tourists and locals from visiting the now infamous resort.

“This area developed around five years ago, when people started building hotels and resorts here. There are now at least eight resorts within a 200-metre radius of this place. Most of the visitors are tourists to the nearby Rajaji National Park. But now, after this incident, this area will be known more for the Ankita murder case,” says an employee of the nearby Panambi Resort & Spa.

Vanantra and the other resorts in the area — with room tariffs ranging from Rs 3,000 to Rs 11,000 — are part of Ganga Bhogpur village. Surrounded by lush green forests, the area is flanked by the Ganga on one side and on the other, the Chilla canal that flows with massive force during the monsoon season.

Right behind Vanantra is a gooseberry processing unit, part of the Swadeshi Ayurveda firm run by Pulkit’s father Vinod Arya. Locals say that this factory came up around 15 years ago. Later, around six years ago, the Aryas built another building and let it out on lease to hotelier Sampa Mukherjee and her husband Anjon Mukherjee, who ran SAM Resorts from the premises

Locals say that Pulkit later ended the lease agreement with the Mukherjee couple, took over the resort and named it ‘Vanantra’. When contacted, Sampa Mukherjee refused to comment on the issue but confirmed that she ran SAM Resort out of the same building.

Down the road from Vanantra, at a roadside tea stall, Sanjay Yadav, a resident of Bhagalpur in Bihar, who used to work at the gooseberry processing unit managed by Pulkit’s wife Swati, says the murder brought the place a lot of attention. But what went unnoticed in the ruckus that followed was that with the resort and the factory shut, many like him have been left in the lurch.

“I came to Rishikesh and joined the factory around a year ago. Our payment for the month of September is pending and now I have lost all hope of getting it. I want to get away from here, go back home, but I don’t have any money,” he says.