Explained | A new ‘smart bandage’ raises the bar for treating chronic wounds

Remember when you fell off a bicycle and got hurt? The wound would have begun open, slowly closing as the body repaired it, restoring the skin to nearly its initial condition. Whether a small scrape, a larger cut, or a burn – our skin can repair itself after injury through a complex wound-healing process. It consists of various stages in which different skin cells participate.

Sometimes, complications from conditions like diabetes, insufficient blood supply, nerve damage, and immune system dysfunction can impair wound healing, resulting in chronic wounds. And irrespective of the underlying cause, all chronic wounds exhibit a disordered healing process and an inability to heal within the expected duration.

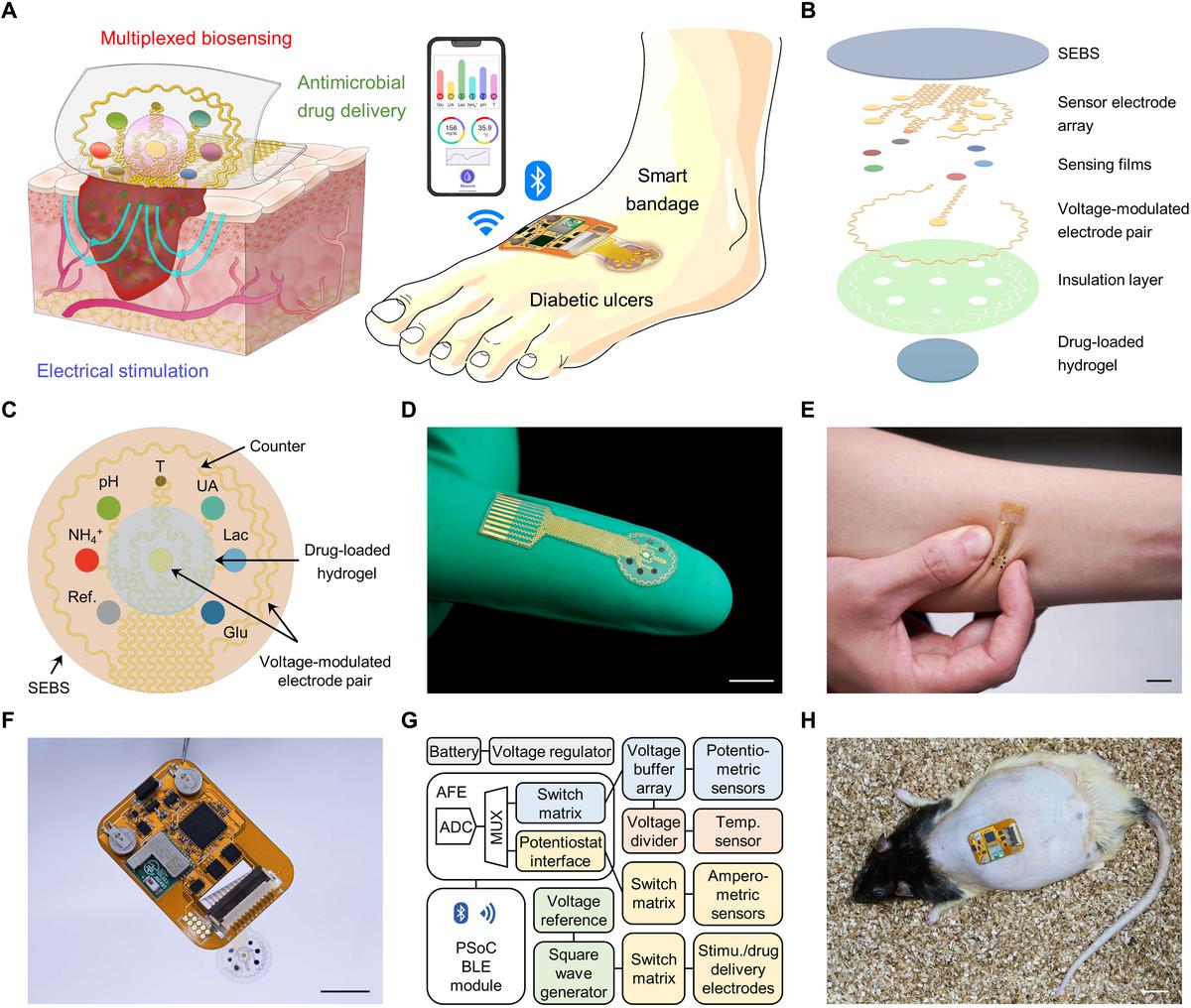

In March 2023, a study was published in Science Advances that offered to help accelerate healing in such cases – using a wearable, wireless, mechanically flexible “smart bandage” as big as a finger. This device, according to researchers, can deliver drugs while monitoring the healing status and transmitting data to a smartphone.

What is a smart bandage?

“Chronic non-healing wounds affect tens of millions of people around the world and cause a staggering financial burden on the health care system,” Wei Gao, assistant professor at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), told The Hindu by email. “Personalised wound management demands both effective wound therapy and close monitoring of crucial wound healing biomarkers in the wound exudate.”

(Exudates are the fluids exiting the wound.)

The device, built in Dr. Gao’s lab, is assembled on a soft, stretchable polymer that helps the bandage maintain contact with and stick to the skin. The bioelectronic system consists of biosensors that monitor biomarkers in the wound exudate.

Data collected by the bandage is passed to a flexible printed circuit board, which relays it wirelessly to a smartphone or tablet for review by a physician. A pair of electrodes control drug release from a hydrogel layer as well as stimulate the wound to encourage tissue regrowth.

The innovation? “Integrating biosensors, soft drug-loaded hydrogels, electrical stimulation modules, and signal processing and wireless communication into a very miniaturised wearable platform that has conformal contact with the skin is highly challenging,” Dr. Gao said.

The result is significant. While scientists have previously used biosensors to track wound-healing, they have monitored a single feature of the wound bed. The new setup, in contrast, can monitor multiple features, building the sort of picture required to fully understand the wound status.

In the past, the exudates have limited the biosensors’ sensitivity. In the new design, the researchers enclosed the sensors in a porous membrane, protecting their parts and increasing their operational stability.

How does the bandage work?

Biosensors determine the wound status by tracking the chemical composition of the exudates, which changes as the wound heals. Additional sensors monitor the pH and temperature for real-time information about the infection and inflammation.

A pair of electrodes – the same electrodes that stimulate the tissue – control the release of drugs from a hydrogel layer. The wireless nature of the device sidesteps the problems of existing electrical stimulation devices, which usually require bulky equipment and wired connections, limiting their clinical use.

The researchers tested the properties of their bandage in vitro. They loaded an antimicrobial substance onto the hydrogel platform, and found it – using the bandage’s features – to be effective against a variety of bacteria commonly associated with chronic wounds. Investigations using skin cells showed that the bandage’s electrical stimulation did enhance tissue regeneration.

When they tested the bandage on wounds in diabetic mice, they found it was able to ‘read’ the infection, inflammation, and metabolic statuses of the wounds. Diabetic rats that received a combination of drugs and electrical stimulation from the bandage also closed their wounds faster, with less scarring compared to rats that didn’t receive this treatment.

Dr. Gao told The Hindu he was surprised by the results. “This is much faster compared to without therapy or using a single type of therapy.”

Does the bandage have limitations?

(A) Schematic of a soft wearable patch on an infected chronic wound on a diabetic foot. (B) Schematic of layer assembly of the wearable patch. (C) Schematic layout of the smart patch consisting of various sensors and electrodes. (D, E) The flexible wearable patch (scale bars 1 cm). (F, G) Schematic diagram (F) and photo (G) of the miniaturised wireless wearable patch. (H) Photo of the fully integrated patch on a diabetic rat with an open wound (scale bar 2 cm).

| Photo Credit:

DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adf7388, CC BY 4.0

However, the team members noted that the mixing of newly secreted chemicals with the old ones delayed the biosensors’ response. They also said the biosensors might require more protection. Another future direction, they added, is scaling up manufacturing and packaging.

Dr. Gao said that the smart bandage will be tested in a clinical setting soon. “We have validated the technology in small animal models and obtained human research protocol approval,” he said. “We are performing human studies in the wound care centre to evaluate the technology in the coming year.”

But Siddharth Jhunjhunwala, a researcher at the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru, doubted whether such a complicated wearable device could really be affordable, although, he added, mass-production could lower its price.

Nonetheless, Dr. Jhunjhunwala – who works on, among other things, drug-delivery systems and biomaterials to modulate immune responses in diabetic wounds – called the study “well-performed and thorough”.

He also said the drug-loaded hydrogel layer responding to electrical stimuli was “cool” even if it wasn’t entirely new.

Where can the bandage be used?

“This is practical to use in a corporate clinical setting,” said Siddhant Vairagar, a cardiac surgery final-year trainee at JIPMER Puducherry. However, like Dr. Jhunjhunwala, he doubts that it will be accessible to people of lower socio-economic strata.

“If a general surgeon sees 10 patients, 3-4 patients will be ones with chronic wounds, so it’s very rampant, and most common in the lower socio-economic strata of the society,” says Dr. Vairagar. “About 80% of people with chronic wounds would be those with diabetes.”

Indeed, about 25% of the nearly 77 million diabetic adults in India develop diabetic foot ulcers, a type of chronic wound. Of these, around half of the wounds become infected, requiring hospitalisation, and about 20% need amputation.

Dr. Vairagar said that even if the bandage is a good product, the patient must be compliant and use it according to the physician’s directions, which may be difficult in a government-facility setting.

He was also sceptical about the added cost if the pathogens in the patient’s wounds resist the antimicrobial peptide in the bandage. “Then we’ll have to change the bandage and add a hydrogel with a different antibiotic, which will incur more cost for the patient,” he said.

What are the bandage’s pros?

But for these challenges, Dr. Vairagar also said that “coming up with a treatment for chronic wounds is always welcome.” The major advantage of this dressing, according to him, is that it doesn’t have to be removed frequently to monitor the status and apply antibiotics.

According to him, “cleaning and dressing the wound increases chances of bacterial contamination every time we open the wound”. So the bandage could also reduce the number of hospital visits.

So Dr. Vairagar suggested a pilot study in a government setup should the smart bandage become available in the market. “The government currently has approved many surgeries and procedures under their insurance schemes,” he added. “If this bandage can be added to the insurance scheme, it can be provided to the ones who need it the most.”

- In March 2023, a study was published in Science Advances that offered to help accelerate healing in such cases – using a wearable, wireless, mechanically flexible “smart bandage” as big as a finger. This device, according to researchers, can deliver drugs while monitoring the healing status and transmitting data to a smartphone.

- The device, built in Dr. Gao’s lab, is assembled on a soft, stretchable polymer that helps the bandage maintain contact with and stick to the skin. The bioelectronic system consists of biosensors that monitor biomarkers in the wound exudate.

- The major advantage of this dressing, according to him, is that it doesn’t have to be removed frequently to monitor the status and apply antibiotics. So the bandage could also reduce the number of hospital visits.

Sneha Khedkar is a biologist-turned freelance science journalist based out of Bengaluru.