Explained | The problem with India’s new guidelines on genetically modified insects

India’s bioeconomy contributes 2.6% to the GDP. In April 2023, the Department of Biotechnology (DBT) released its ‘Bioeconomy Report 2022’ report, envisioning this contribution to be closer to 5% by 2030. This ambitious leap – of $220 billion in eight years – will require aggressive investment and policy support. But neither funding for the DBT, India’s primary promoter of biotechnology, nor its recent policies reflect any serious intention to uplift this sector. Along with more money, policies that enable risk-taking appetite within Indian scientists will be required to create an ecosystem of innovation and industrial action.

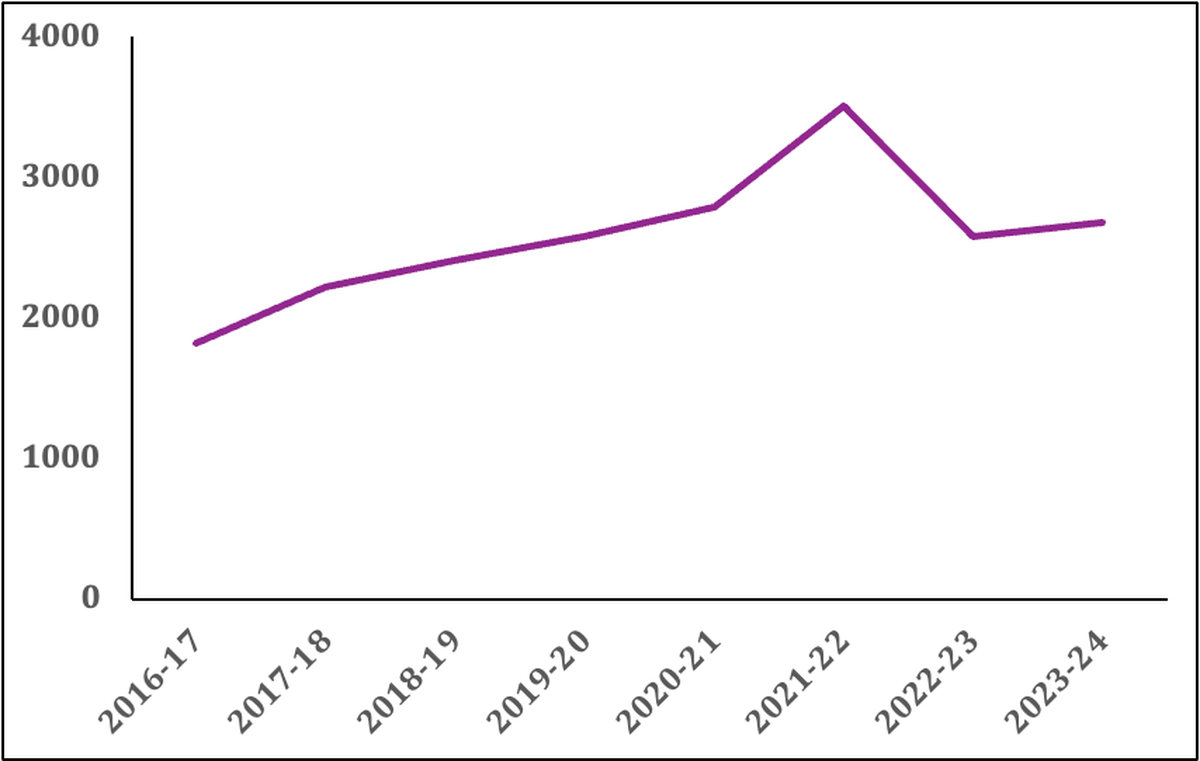

Funding for biotechnology India has been stagnating for a while. Despite a slight uptick during COVID-19, when DBT led the vaccine and diagnostics efforts, funding hasn’t returned to the pre-pandemic level. The current allocation is also only 0.0001% of India’s GDP, and it needs to be significantly revised if biotechnology is to be of any serious consequence for the economy.

Allocation for DBT (budget estimates) across designated years (in crores of rupees).

| Photo Credit:

Author provided

The reduced funding is detrimental to India’s national interests as well, considering the DBT is essential to any pandemic preparedness efforts. Further efforts are also needed to attract private funding in biotechnology research and development, a key area that industry representatives, investors, and government officials have highlighted multiple times.

Funding aside, biotechnology policies also need to be aligned to the economic goals set out in the Bioeconomy report. However, the language in a set of guidelines that the Indian government released recently, pertaining to genetically edited insects, indicate a problem.

In April 2023, the Department of Biotechnology (DBT) issued the ‘Guidelines for Genetically Engineered (GE) Insects’. They provide procedural roadmaps for those interested in creating GE insects. They have three issues, however.

First: Uncertainty of purpose

The guidelines note that GE insects are becoming globally available and are intended to help Indian researchers navigate regulatory requirements. However, the guidelines don’t specify the purposes for which GE insects may be approved in India or how the DBT, as a promoter of biotechnology, envisions their use.

The guidelines only provide regulatory procedures for R&D on insects with some beneficial applications. The introduction states:

“The development and release of GE insects offers applications in various fields such as vector management in human and livestock health; management of major crop insect pests; maintenance and improvement of human health and the environment through a reduction in the use of chemicals; production of proteins for healthcare purposes; genetic improvement of beneficial insects like predators, parasitoids, pollinators (e.g. honey bee) or productive insects (e.g. silkworm, lac insect).”

That is, the emphasis of using GE insects appears to be on uplifting the standard of living by reducing disease burden, enabling food security and conserving the environment. While these are all necessary functions, current biotechnology-based policies are not in sync with the broader commitment to contributing to the bioeconomy.

The guidelines – which are more procedural in nature than indicative of governmental policy – set out forms and instructions for using GE insects of various types. The approval for these experiments comes under the broad ambit of the Review Committee on Genetic Manipulation, a body under the DBT.

The guidelines have been harmonised to guidance from the World Health Organisation on GE mosquitoes. GE mosquitoes represent the most advanced application for this technology – yet the guidelines seem to downplay the economic opportunities that such insects provide.

Engineering honey bees to make better-quality and/or quantities of honey will help reduce imports and also maybe facilitate exports. Similarly, GE silkworms may be used to produce finer and/or cheaper silk, affecting prices and boosting sales. But the guidelines and policy are both quiet on how GE insects can benefit the bioeconomy and for which purposes the government might approve the insects’ release.

Second: Uncertainty for researchers

The guidelines are applicable only to research and not to confined trials or deployment. That is, once the insects are ‘made’ and tested in the laboratory, researchers can conduct trials with them on the approval of theGenetic Engineering Appraisal Committee (GEAC), of the Union Environment Ministry.

Government authorities will also have to closely follow the deployment of these insects. Once deployed, GE insects can’t be recalled, and unlike genetically modified foods, they are not amenable to individual consumer choice. For example, if a consumer doesn’t want to eat a GM organism, she can choose to buy organic food or food labelled “contains no GMO”. But if a company decides to release a GE insect in an individual’s neighbourhood, she will have no choice but to be exposed to it. So wider community engagement and monitoring of the impact of GE will be required.

The nature of the technology products – i.e. mosquitoes, honey bees, etc. – also make their private use difficult. In any case, the government will be the primary buyer in many cases, such as ‘GE mosquitoes for disease alleviation’ or ‘honey bees for increased pollination’. But then there’s no clarity on whether the Environment Ministry will actually approve the deployment of GE insects or what criteria it might use to consider a proposal to do so.

For example, while researchers have developed and tested GE mosquitoes to alleviate malaria in foreign settings, we don’t know if the solution will be feasible in India. On the other hand, as honey bees populations decrease, genetically edited honey bees which live longer, might be of use in India. But if there is no clarity on which idea the government would support, why would anyone invest in research on such insects?

On a related note, the guidelines define GE insects by their risk group and not by the end product. It makes sense to subject any GE insects for human/animal consumption to stringent checks – but why using insects for silk or lac production needs to be checked the same way is not clear. The guidelines can sidestep this by adapting its rules for genetically modified crops for non-consumption purposes.

Third: Uncertainty of ambit

The guidelines offer standard operating procedures for GE mosquitoes, crop pests, and beneficial insects – but what ‘beneficial’ means, in the context of GE insects, is not clear.

The lack of clarity about the insects and the modifications to them that are deemed ‘beneficial’ will impede funders and scientists from investing in this research. In a country with low public as well as private funding, the absence of a precise stance to identify and promote research priorities hampers progress.

Other gene-editing guidelines contain similar ambiguity, such as the National Guidelines for Gene Therapy Product Development and Clinical Trials. They identify a gene-therapy product as “any entity which includes a nucleic acid component being delivered by various means for therapeutic benefit”. But they don’t “define therapeutic benefit”, creating confusion on which gene therapy products will actually be permitted.

Further, genetic engineering can also be used to unintentionally generate malicious products. In 2016, the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency floated an ‘Insect Allies’ programme with the idea of creating insect vectors to deliver gene-editing components to plants that are threatened by pests. Scientists quickly pointed out that this application could also be used to create bioweapons. Similarly, the new guidelines don’t sufficiently account for more dangerous possibilities.

So as things stand, the guidelines are not in sync with the ambitions outlined in the Bioeconomy 2022 report.

Shambhavi Naik is a researcher at The Takshashila Institution.

- India’s bioeconomy contributes 2.6% to the GDP. In April 2023, the Department of Biotechnology (DBT) released its ‘Bioeconomy Report 2022’ report, envisioning this contribution to be closer to 5% by 2030. This ambitious leap – of $220 billion in eight years – will require aggressive investment and policy support.

- Funding for biotechnology India has been stagnating for a while. Despite a slight uptick during COVID-19, when DBT led the vaccine and diagnostics efforts, funding hasn’t returned to the pre-pandemic level.

- The guidelines note that GE insects are becoming globally available and are intended to help Indian researchers navigate regulatory requirements. However, the guidelines don’t specify the purposes for which GE insects may be approved in India or how the DBT, as a promoter of biotechnology, envisions their use.