Getting a closer look at Pluto

The most detailed view up till 2010 of the entire surface of the dwarf planet Pluto. It was constructed from multiple NASA Hubble Space Telescope photographs taken from 2002 to 2003 and released on February 4, 2010.

| Photo Credit: HO

Come February 18, and it will be 94 years since we’ve known of the existence of Pluto. Pluto has enjoyed popularity with the public throughout its known existence. Right from the time it was discovered in 1930 and hailed as the ninth planet, through to 2006 when it was demoted to the status of a dwarf planet, and since, Pluto has held the imagination of the masses.

Pluto takes nearly 248 years to orbit around the sun and its elongated orbit ensures that it is about 7.3 billion kilometres from the sun at its farthest and gets closest when it is about 4.4 billion kilometres from it! With its closest distance to the sun in itself being very very far, this Kuiper belt object is naturally very distant from Earth as well.

So far, in fact, that trying to see and resolve the surface of Pluto from Earth is akin to trying to see the print on a ball when the ball is placed over 50 km away! Pluto’s disk is so small that it can’t be resolved from beneath the Earth’s atmosphere. We are not just talking about plain viewing, but also using the most powerful ground-based telescopes.

Hubble comes to the rescue

It was a space-based telescope in the form of the Hubble Space Telescope that enabled the first unobstructed viewing of Pluto. Tasked with observing and imaging the planet in June-July 1994 (remember that it was still a planet back then), it was put together and released for public consumption on March 7, 1996.

The Hubble Space Telescope was tasked with snapping Pluto again in 2002-2003. Astronomers had installed in it a new camera called the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS). This new camera was equipped with an operating mode called the High-Resolution Camera (HRC). The ACS/HRC system produced 384 images of Pluto – the most detailed set of observations made of Pluto until then.

These raw images were then worked on by scientists and engineers for years on end before they were eventually released to the public on February 4, 2010. This set of images were, until then, the most detailed ever of Pluto.

Special algorithms

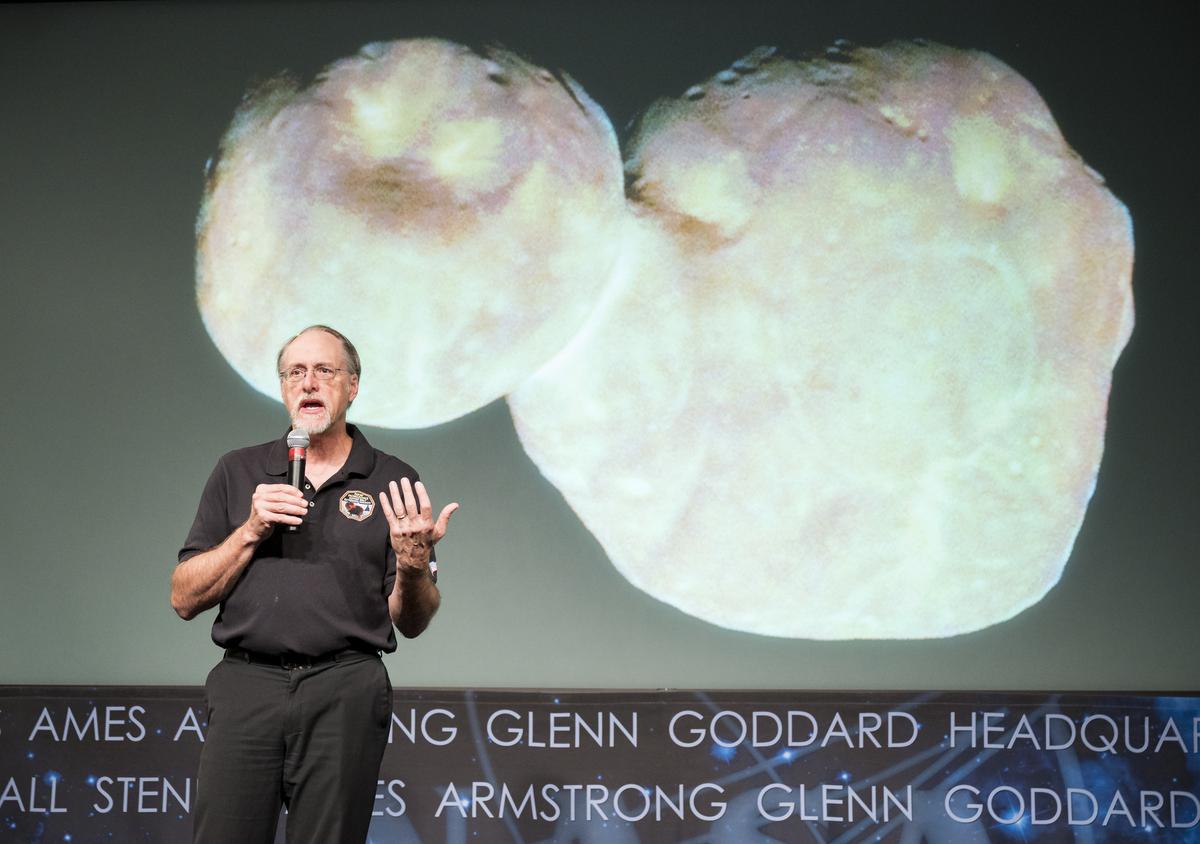

Marc Buie, who was also part of the New Horizons Discovery Team, speaks at a naming ceremony for 2014 MU69, a celestial body discovered by the New Horizons mission and Hubble Space Telescope, formerly nicknamed “Ultima Thule”, in November 2019.

| Photo Credit:

NASA/Aubrey Gemignani

“This has taken four years and 20 computers operating continuously and simultaneously to accomplish,” said lead investigator Mark Buie of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado at a NASA press conference on that day. Even though Buie, who had developed special algorithms to sharpen the Hubble data, put it across in just a statement at the press conference, he went into more details when writing about this research project for his website.

While speaking about the technique employed to get the best out of the raw images, Buie mentions the difficulty involved in working with the ACS data. The idea is to start with a guess of Pluto’s map and arrive at the best map using the data and a computer.

It all adds up

The process of dithering combines multiple, slightly offset pictures to generate a higher resolution view. While that might sound easy, “taking the map and computing what one image must look like took about 5 seconds on a circa 2004 computer.” Since it took five seconds to process one image on one of the most powerful computers of the time, it would add up to 30 minutes to test one guess for the map with all 384 images. Buie realised that at this rate, he would need 20 years on one computer to arrive at an answer.

To overcome this obstacle, Buie came up with a scheme by working with a great programmer, Doug Loucks. They maximised the computing power by utilising parallel processing. In their scheme, there was one computer that worked as the master – pulling all data together and producing the final answer, another that worked as a foreman – listening to the master and handing off tasks to workers who were not busy, and the rest were workers. The computers that served as foreman and workers didn’t really know what they were doing and were like puppets in the hands of a puppeteer – the master computer.

It still took them years to arrive at the final answer, which they released to the public in February 2010. In addition to being the sharpest images of the dwarf planet until months before the New Horizons spacecraft made its Pluto flyby in 2015, these images also helped the scientists plan for that flyby.