A peek into maestro S. Ramanathan’s life and music

The legendary musician Dr. S. Ramanathan.

| Photo Credit: D_KRISHNAN

By catching talents young and nurturing their skills in groups, S. Ramanathan adhered to the Suzuki method of education that earned Carnatic music eminent practitioners of varying styles, according to the late musician’s granddaughter and vocalist S. Sucharithra. Letting his students choose their tuition time on a first-come-first-serve basis at his Chennai home, the pedagogy was a classic instance of creating the right learning environment, said Sucharithra in her two-hour talk titled ‘A Day with Dr S. Ramanathan’ at Ragasudha Hall under the aegis of Parivardhini on April 6.

Ramanathan (1917-88) never kept exclusive slots for seniors, juniors or beginners among his students. Neither did he encourage notating while teaching ragas or compositions; instead upheld the strength of oral tradition in Carnatic music. These showed his allegiance to the Talent Education formulated by Japanese violinist Shinichi Suzuki (1898-1998) whose philosophy prescribed educating people of all levels of ability, promoting peer relationships and listening to music routinely.

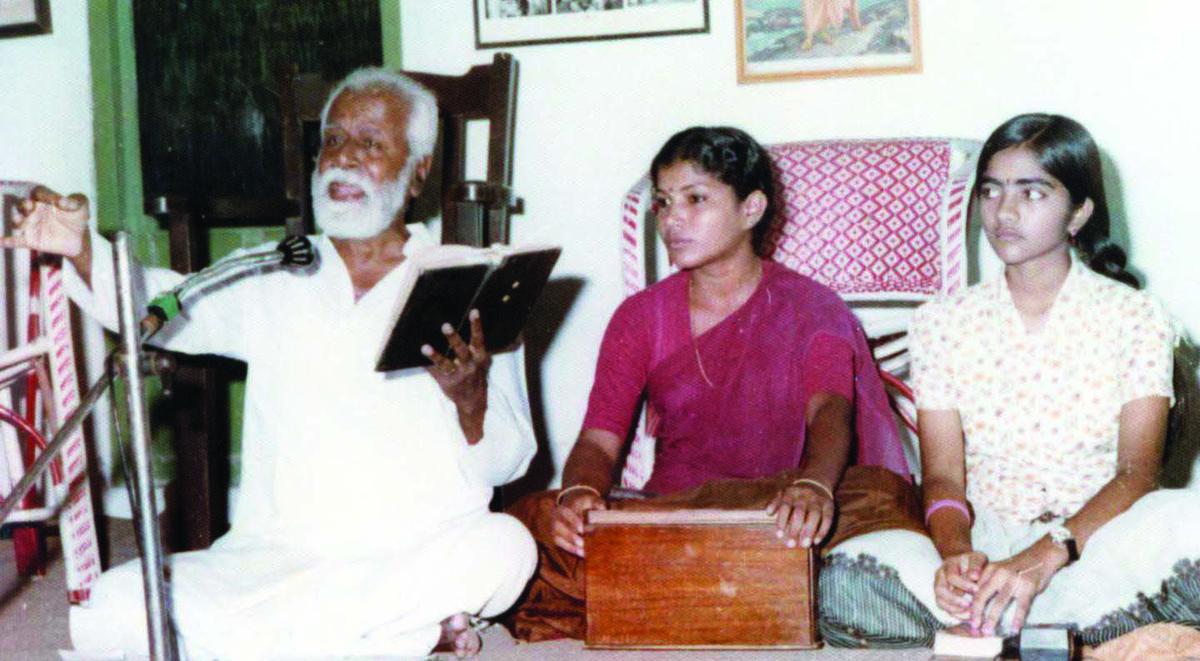

Young Sowmya with her guru Dr. S. Ramanathan and his daughter Vanathi

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

The first teaching session of a typical day at Ramanathan’s modest house would begin at 6.30 a.m. Once this batch of eight to ten students disburses, there will be a two-hour training session ending at 10 a.m. This will be followed by lessons on the veena, in which too he had expertise. Then there would be evening and night classes. Besides home tuitions there would be lectures at institutions such as the Kalakshetra and Kalapeetham, recalled Sucharithra.

The scholar’s day typically began around 5 a.m. with practice on the violin. “We kids would be in the room, playing. Our mischiefs least irked grandpa,” reminisced Sucharitha, whose father is the famed recordist HMV Raghu (K.S. Raghunathan). At peak noon, even if the sun is merciless, Ramanathan will go for his walk, and on his way back would attend to household errands. “He’d be soaked in sweat, but never once cribbed about the weather.” Food used to be dietary; never fancy. Late afternoons will be spent reading research material.

Ramanathan had a “photographic memory” about books, says Sucharithra. “He would clarify doubts by referencing specific pages of books. Equally amazing was his eminence in drawing conclusions by linking nuggets of knowledge.” When Ramanathan arrived in Chennai in the mid-1970s after his association with Sathguru Sangeetha Samajam in Madurai, he brought in a “lorry-load” of tomes. Fascinated perpetually by the beauty of music — not just of Carnatic — Ramanathan never engaged in small talks. “None heard him speaking ill or even making jokes belittling any fellow musician. He was kind, humble and approachable.”

During Margazhi festivals, Ramanathan had a busy schedule. It didn’t include just sabha concerts, he was keen in promoting the bhajana sampradaya, and would participate in unchavritti in mada veedhis around the Kapaleeshwarar temple in Mylapore. Ramanathan was keen to know more about pre-Tyagaraja compositions, delving deep into Bhadrachalam Ramadas, Annamacharya and Purandara Dasa, among others. While popularising vintage kavadichinthu, he also tuned kritis by contemporaries such as Ambujam Krishna and Tulasivanam Ramachandran Nair. With an open throat and penchant for straight notes, his vocals “never generated surplus sangatis,” as violinist M. Chandrasekharan used to hail. Sucharithra substantiated certain highlights of Ramanathan by playing his records. Not finding mention, though, was the ethnomusicologist’s US days in Wesleyan University, which conferred him a doctorate.