Ebrahim Alkazi and his secular approach to theatre

The lines between personal and professional blur, engage and intertwine at every turn of the page in Amal Allana’s biographical novel Ebrahim Alkazi: Holding Time Captive, which traces the quintessential identity of the father of modern Indian theatre — Ebrahim Alkazi. “You can’t talk of my father on a personal level alone, because his work was an intrinsic part of his life,” says Amal, Ebrahim’s daughter, who took nearly 10 years to come up with the book that finds its roots in a 2016 exhibition titled The Theatre of E. Alkazi. “I never quite started out to write a book as I had never written a book before; it all started with the exhibition,” she shares, touring our mind through a copious collection of Alkazi’s photographs and artworks found in a tin trunk, which she chronicled to chart the trajectory of her father’s works. Before making their way into the book, these contents would be displayed at yet another exhibition The Other Line (2019) showcasing over hundred drawings and paintings of the theatre doyen just a year before he died on August 4, 2020.

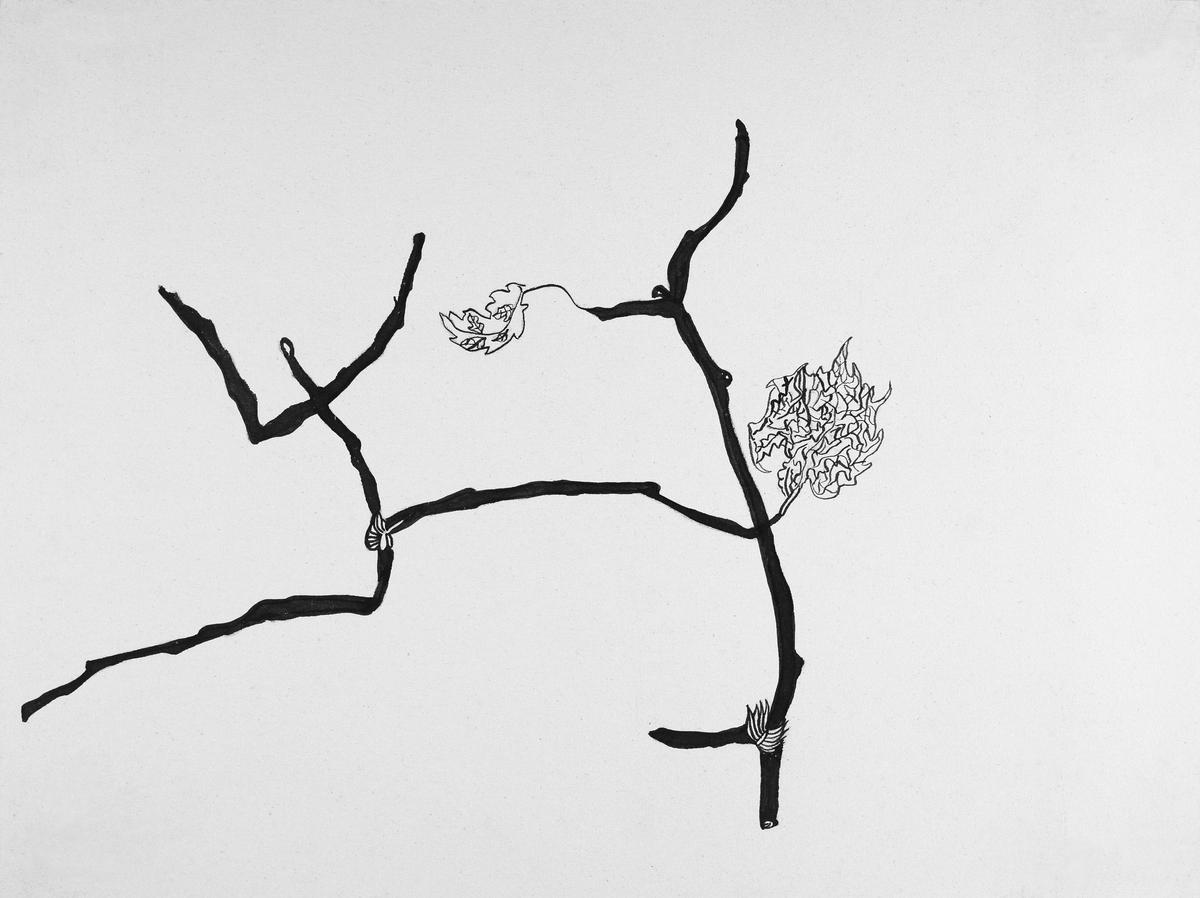

Lovers II, drawing by E. Alkazi, 1950

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy: The Alkazi Collection of Art

“We were in New York in 1999, when my father agreed to my request of interviewing him. We put up a static camera and I started asking him questions. Looking back, I would have asked him many more questions, which I later never got the opportunity to,” says Amal, justifying the dialogues that run parallel to the narration of events that contributed to the making of Ebrahim Alkazi. She attributes the conversations cited in the book to many of Ebrahim’s friends — thespians, writers, critics and members of the Progressive Artists’ Group — and his wife Roshen Padamsee. “I spoke with them too. The book is not the telling of a tale, I am making it alive, I am making scenes. I am a theatre director and I have an instinctive feeling to convert everything into a play or a scene. That was the best part about writing this book; it was like I was writing a long play,” she says describing the book’s literary form.

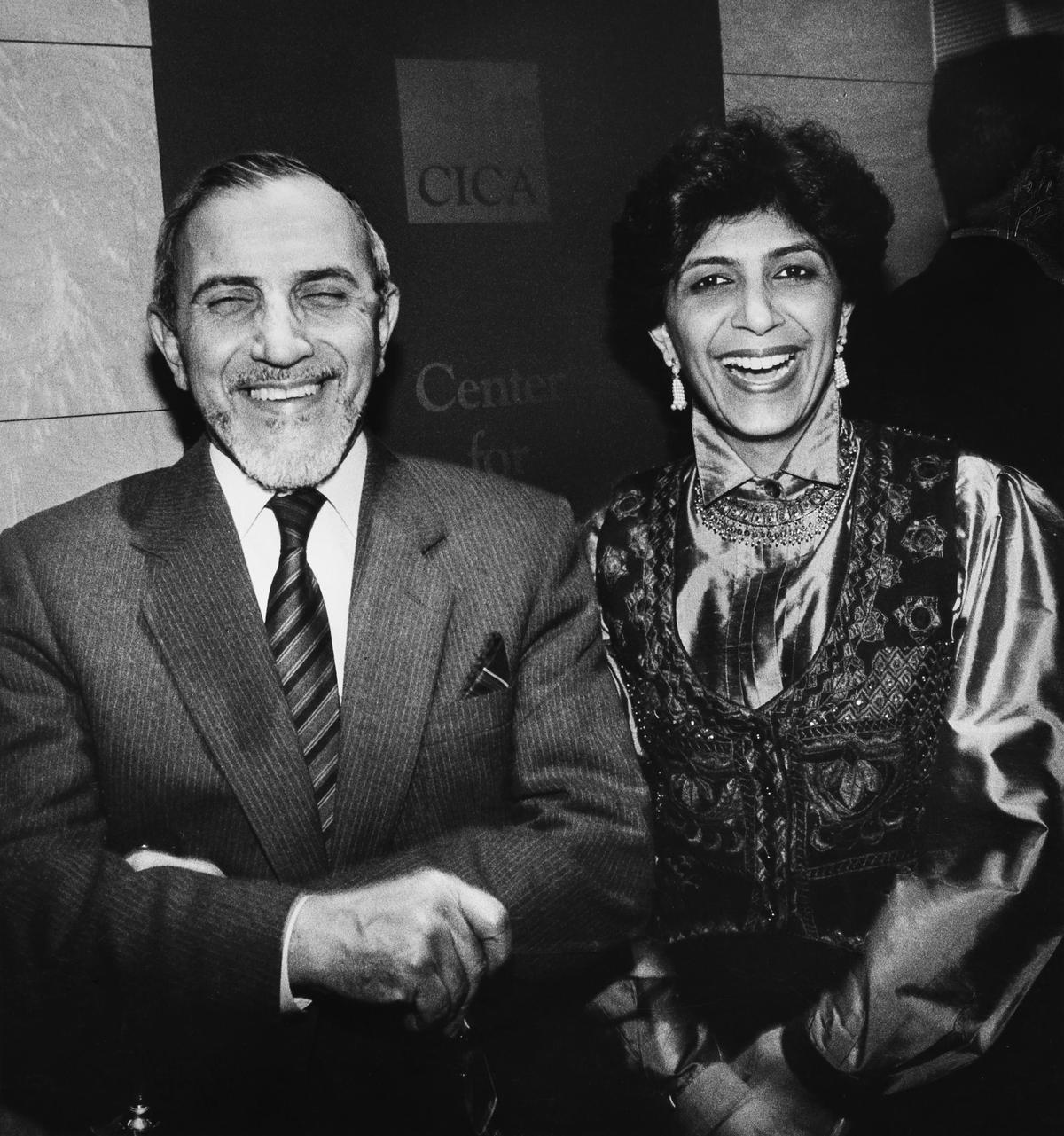

Ebrahim with Amal Allana.

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Amal inherits her love for theatre from her father, also his interest in various creative mediums of art. She was the chairperson of the country’s premier theatre educational institute National School of Drama (NSD), which was founded in 1959 and Alkazi was invited to head it in 1962. She founded Dramatic Art and Design Academy (DADA), New Delhi, with her husband Nissar Allana, in 2000. Amal also runs Art Heritage Gallery. “I draw from him the whole discipline of theatre, looking at theatre as part of many art forms, the idea of drawing from world traditions (and not just India) and of being inclusive,” she says. The writer in her emphasises on the last bit of the above-mentioned quote — she fervently unfolds the layers of Ebrahim’s cultural, nationalistic and artistic identity, starting from his roots in Bombay as the son of a migrant from Saudi Arab.

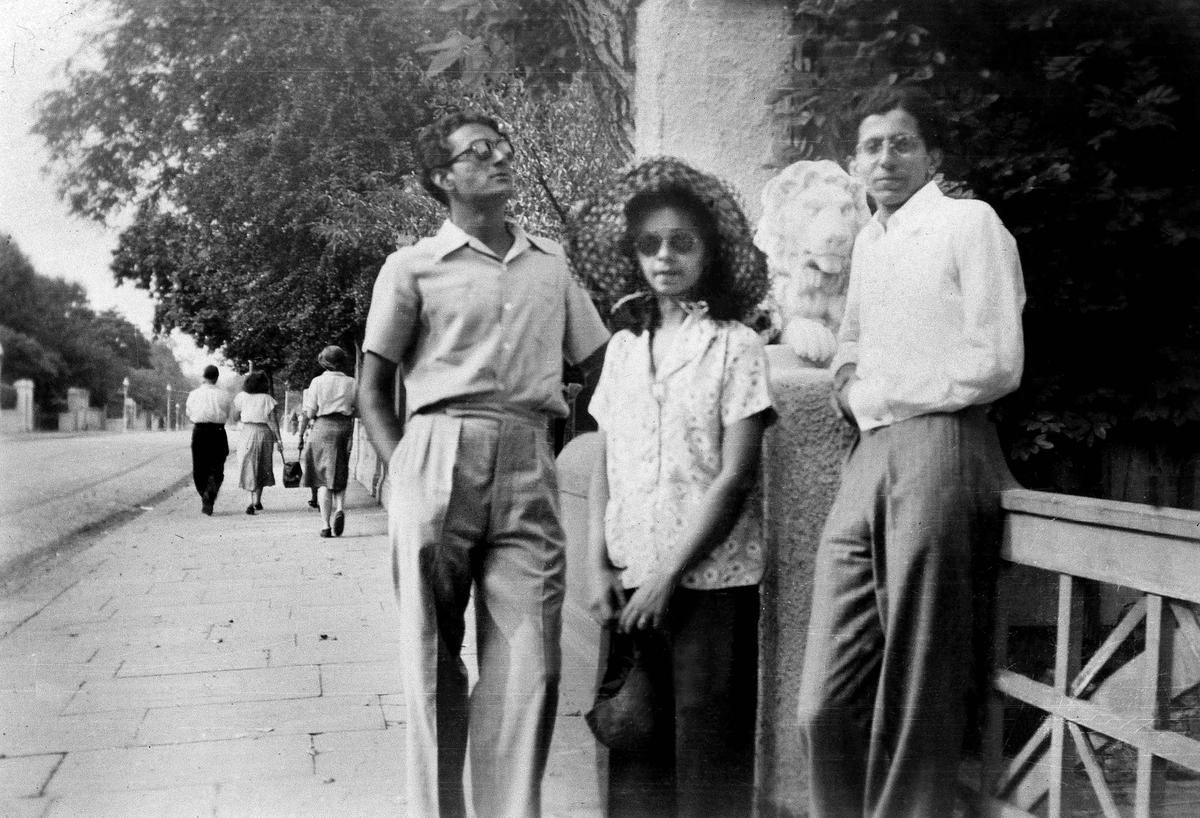

Roshen with Nissim Ezekiel and Baloo in London, 1949

Courtesy: Alkazi Personal Archives

| Photo Credit:

Alkazi Personal Archives

“Despite the fact that Alkazi was not an Indian by parentage, being the son of a Saudi Arab immigrant, his sense of belonging to India only intensified over the years. His parents left for Karachi after Partition, but he remained in India. Also, I was named Uma; there was no question of Hindu and Muslim. My mother wore a bindi. You couldn’t tell that she is a Muslim or Khoja – those were different days, we grew up in a society, a family where there were no differences. My father’s friends were Catholics, Muslims, and Hindus, no one was looking at anyone’s religion. We have to understand that as Indians we come from a very rich past and the richness comes from it being syncretic,” she explains, adding that the book means to expose the younger generation that there was another way of life.

Love for literature

The book evolves with more nuanced citations of Ebrahim’s artistic and academic endeavours, building on his younger days — his love for literature, yearning for an Indian identity which stands validated by a Parsi man while attending Gandhi’s Quit India rally, and his initiation into the world of theatre after meeting Sultan Padamsee (whose sister he later married). After Sultan’s death, he leaves for London to study art but ends up enrolling for theatre at Royal Academy of Dramatic Art only to return to India later. “Alkazi, being the man of his time, was imbibing the art trends of ’40s, like Gesamptkunstwerks, where many art mediums such as poetry, painting, writing and theatre were being combined with one another to make one total, integrated piece of art. You had Picasso and Henri Matisse designing theatre sets. So, when Ebrahim came back to India, he invited M. F. Husain to design the set of his first play Murder in the Cathedral. Then artists like Vasudeo S. Gaitonde and Akbar Padamsee designed sets for him too,” she adds.

Murder in the Cathedral by T. S. Eliot, dir. E. Alkazi, set design by M.F Husain, Theatre Group, Bombay, 1953

Courtesy: Alkazi Theatre Archives

| Photo Credit:

Alkazi Theatre Archives

Amal’s book tenders one more interesting aspect of Ebrahim’s disposition — of taking people along with him. He not only got his father to sponsor Nissim Ezekiel’s trip to London, but also had FN Souza for a flatmate at his accommodation at 38 Lansdowne Crescent. “He was always inviting artists from different fields to collaborate with him. This led to him conceiving of integrated theatre courses that included a study of dance, mime, literature and the visual arts in his Bombay years. Later, these ideas were developed to create a more detailed syllabus for a three-year course in theatre studies at NSD. He was also keen on housing the institute in Rabindra Bhawan, to share the space with Sangeet Natak Akademi, Sahitya Akademi and the Lalit Kala Akademi,” says Amal.

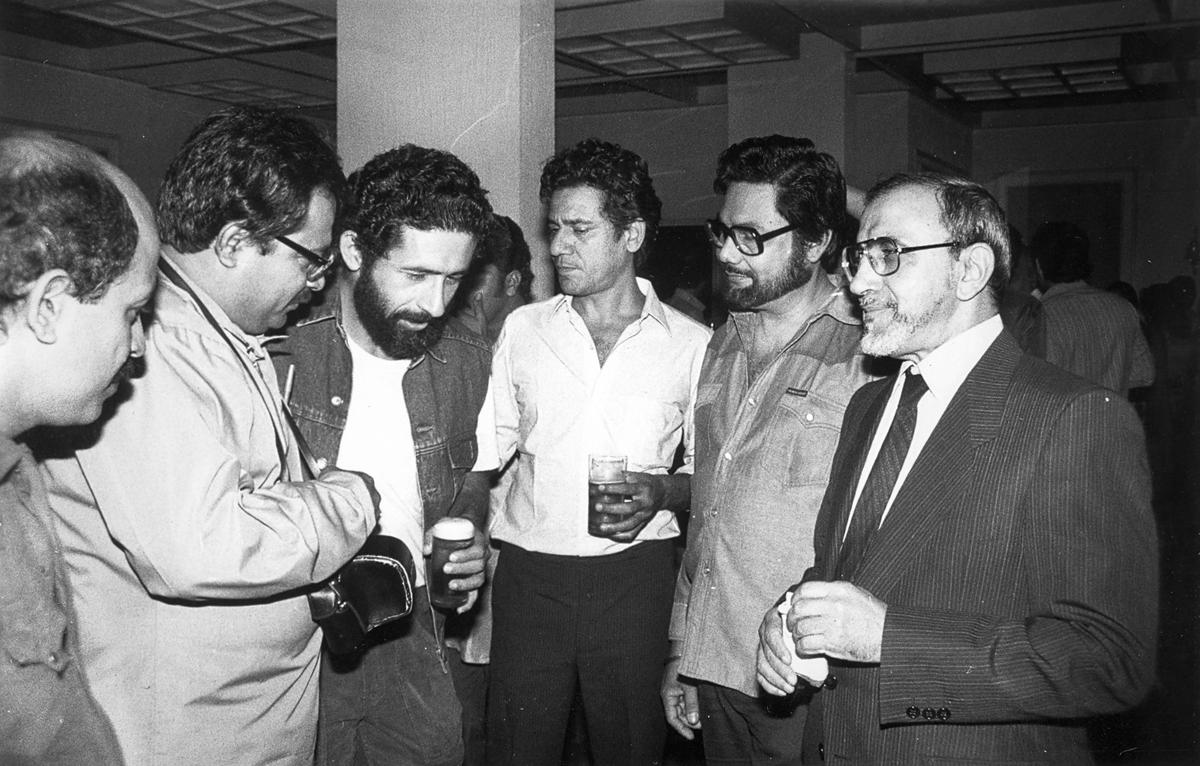

Alkazi with former NSD students, including Naseeruddin Shah and Om Puri, at a reception in his honour in Bombay

Courtesy: Nadira and Raj Babbar

| Photo Credit:

Nadira and Raj Babbar

Alkazi resigned from NSD on May 11, 1977. In her book, Amal states: “It was not the virulent critics, not theatre people, nor his own beloved students who prompted him to take the final step. It was his realization that the pettiness of those in power could not find it in themselves to support his brand of futuristic schemes. Tremendously pained that this, in fact, was the new harsh reality, he said of a moribund bureaucracy: There is a lot that our commissars of culture in the last 20 years have to answer for, and history is not going to let them off lightly. They have vitiated the national cultural scene with their pettiness and paranoia; their own embittered frustration; their sickening hysteria. They have crammed the akademis and other cultural bodies of the government with incompetent, servile functionaries; they have reduced them to dismal, arid, fetid charnel houses of culture….”

Rendezvous with Amal

Literature Live! and Penguin Random House India, in association with The Royal Opera House, Mumbai and Avid Learning have announced the Mumbai launch of Ebrahim Alkazi: Holding Time Captive by Amal Allana. After the book launch, the author will be in a riveting conversation with poet, curator, and cultural theorist Ranjit Hoskote, unraveling the multifaceted influence of one of the giants of twentieth-century theatre and a key promoter of the visual arts movement in India. The evening will be elevated by the distinguished presence of filmmaker Shyam Benegal as the chief guest, accompanied by enthralling readings from singer-composer Sonam Kalra and director and actor Rehaan Engineer.

Where: Royal Opera House, Mumbai

When: Wednesday, April 17 | 6.30pm to 8pm

RSVP: www.avidlearning.in

Amal believes that the lack of financial support to Indian theatre has eclipsed its popularity, which is not so much the case with other art forms. “What’s worrying at the moment in the art world is that the threat does not only come from political thinking on free expression. It also comes from the fact that art has over the last decade become a commodity, an investment, where the market defines what is good art or fashionable art. It’s the opposite in theatre. No one earns from theatre. Yet, one hears of sporadic incidents where certain plays have been censored,” she says, while reflecting on the nature of art content.

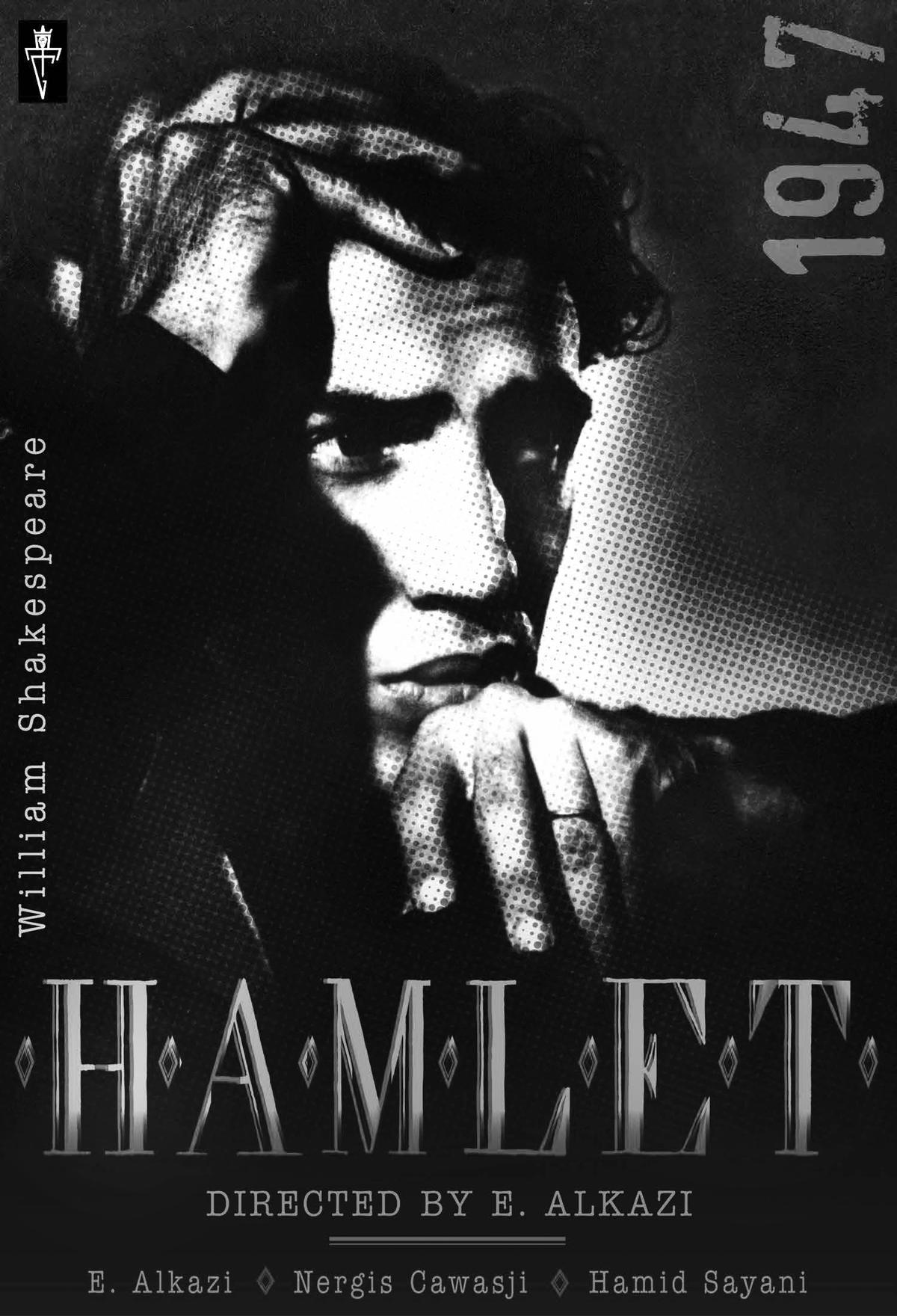

Poster of Hamlet by Shakespeare, dir. E. Alkazi; Alkazi as Hamlet, Theatre Group, Bombay, 1947

Courtesy: Alkazi Theatre Archives

| Photo Credit:

Alkazi Theatre Archives

She is driven back to the post-World War II era when artists in Germany went underground. “When someone tries to stifle you, you find new ways of expression. It births innovation which can spur a new movement. In theatre too there are so many new plays, by small groups, like the ones we saw at the recently held Mahindra Excellence in Theatre Awards. Like this we need more private people and of course the government to support theatre, which is a very expensive activity. We are a bit like the farmers,” she feels, and suggests that the government must subsidise theatre. “We have a lot of talent in our country, and so many issues to talk about and discuss. Theatre is the correct medium for these conversations,” she signs off.