Still feels like a dream: Rintu Thomas

Rintu Thomas calls her award-winning film, Writing with Fire, co-directed with her partner Sushmit Ghosh under their Black Ticket Films banner, “literally the first offspring we had.” The couple, who got married in 2015, started working on it the year after and went on to spend the next five years with it, travelling to rural Uttar Pradesh repeatedly to shoot. “My mother is not happy with the comparison,” says Rintu who was here in the city last month for a screening of the film at the Bangalore International Centre in collaboration with Vikalp, Bengaluru. “But after 13 years of making films, this is our first feature film together.”

Writing with Fire is a gripping, beautifully shot film, focusing on the lives and work of three journalists who are part of Khabar Lahariya, an independent, media organisation run entirely by Dalit women. “At its heart, the film is a meditation on power,” she says, of what she calls an intersectional film infused with hope. “We knew once it was made, a diverse audience would resonate with it.”

The three women, whose stories unfurl over the course of the film, are very different: the most senior, Meera Devi, is confident and self-assured, the much younger Suneeta Prajapati is dynamic and feisty while the third, Shyamkali Devi, though more reticent than her colleagues, is incredibly hardworking and tenacious.

“The fact that the three of them had very different personalities and personal histories added to the triptych we wanted. Yet, at the same time, there was a common thread between all of them: believing in journalism as an act of justice,” says Rintu, adding that the filmmakers had chosen the women based on their own unique voices and styles. The film looked at these three women as journalists as well as offered viewers a glimpse into their personal worlds, she adds. “It was the professional and the personal in a symphony with each other.”

Going by the number of awards and accolades the film has been garnering, including an Academy Award nomination, two Sundance wins and most recently, a Peabody Award in the documentary category in May. “Everything that has happened around the film still feels like a dream,” she adds. “You hope, and you create, but you never think such a journey will happen.”

Documenting the world

A still from the film

| Photo Credit:

Black Ticket Films

Rintu and Sushmit met at Jamia Millia Islamia University, where they were both studying mass communications, graduating in 2008. “It was a very dynamic space,” remembers Rintu, adding that the first film they made together was a student documentary called Flying Inside My Body, a film about the photographer and queer activist, Sunil Gupta. “That was the beginning of our working relationship,” she says.

In 2009, soon after graduating, they started Black Ticket Films, a film production company focusing mostly on non-fiction, a decision which was met with some trepidation from their peers and friends, “We were at the very beginning of our careers and had no resources. People asked us what was wrong with us,” remembers Rintu, pointing out that non-fiction, in general, does not garner larger audiences, a phenomenon that is changing but very slowly. “The genre ends up not interacting with people’s daily entertainment appetite. Unlike, say a commercial Hindi film which is easily accessible. The central challenge is access,” she says, pointing out that the latter can be easily watched on a flight or in a cinema hall.

Documentaries, on the other hand, are not so easily available. “Often, even the audience that may want to watch the film doesn’t know that it exists. This is a big gap,” she says, adding that with Black Ticket Films, they hoped to make documentaries that are accessible and exciting. “When you are younger, you earnestly think you can change the world,” she says, wryly. “It is a heavy, tall claim to make but that foolhardiness is nice. I look back now at that resilience, and I am quite amazed at that.”

Those early risks paid off, however. Today, 14 years later, Black Ticket Films has won multiple awards and grants and made over 130 short films to date. “We built a team and now have a body of work that pulsates with the sinews of our vision,” says Rintu. “I am proud of this.”

Of stories and more

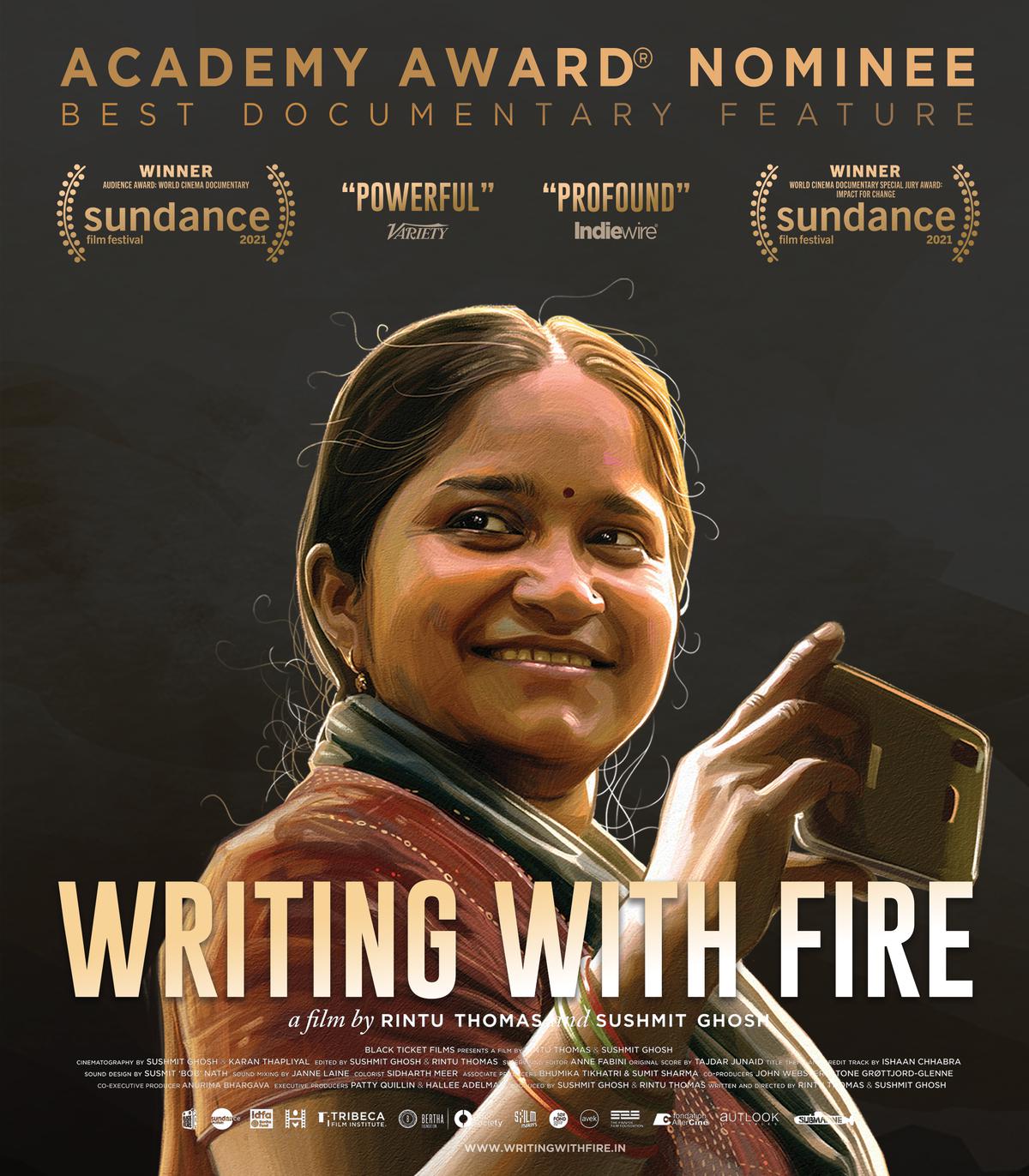

The film poster

| Photo Credit:

Black Ticket Films

It began with a photograph: an image of a woman walking across the parched landscape of Uttar Pradesh, a newspaper in her hand. This was how Rintu and Sushmit were first introduced to Khabar Lahariya, a media organisation run by women in a society that was not necessarily open to the idea of female journalists. “We reached out to the Khabar Lahariya team in Delhi,” says Rintu, adding that they were then invited to be part of a critical meeting that the reporting team was having. “The leadership was discussing the pivot to digital,” remembers Rintu.

Rintu and Sushmit, accompanied by their long-time collaborator, cinematographer Karan Thapliyal, decided to take the train down to Bundelkhand in UP to be part of this meeting. “We decided to take our camera, which is pretty rare for a first day of recce,” says Rintu. “But the team said the meeting would be pretty historic so we did,” she says.

This meeting becomes the starting point of the documentary, which then delves into the lives and work of Meera, Suneeta and Shyamkali, in a fly-on-the-wall way, a conscious choice, says Rintu. “We started with the sit-down interview format, but it felt very disingenuous. It wasn’t really capturing the energy of the story.”

Instead, the team got rid of their tripods and simply shadowed these women, spending time with them and filming their work in the field, and their interactions with their family and each other. “We wanted to make it more visceral…to show and not tell,” she says, pointing out that it was important to make someone outside the reality of these women really feel what it means to be a marginalised woman in those parts. This creative choice also enables a nuanced portrait of the landscape in which it is shot to emerge: a space bristling with violence, misogyny and injustice, but also possessing a stark beauty. “The journey is a leitmotif in a film. It allowed us to talk about UP in a non-stereotypical way.”

It was challenging right from the beginning, and the challenges never did end. From struggling to garner funding to editing footage shot over five years, negotiating this landscape as an obvious outsider and facing the controversy that the Oscar win brought, with the Khabar Lahariya team issuing a statement that they were misrepresented in the film, it has not been an easy road. “It was frustrating at times,” she admits. “But honestly, at no point did we think we would stop.”

Talking about the controversy, Rintu says, “We went into making this film mindfully and slowly, taking five years, believing that the emotional energy of the narrative would come from intimacy, which is the result of trust built slowly over time,” she says, pointing out that as documentary filmmakers they were fully aware of the fact that they were always in a reality that is not their own. “There is an inherent power imbalance that is endemic to the non-fiction form.”

During production, editing and distribution of the film, they included processes aimed at making it as collaborative as possible, she adds. However, it was also important that they stayed independent, something that was discussed. “One of the first conversations we had was about having an independent lens, which as independent journalists they respected.”

The participants of the film travelled and represented the film globally for over a year but their leadership felt the need to distance from it in the week of the Academy Awards, something that the filmmakers see as an “act of self-preservation,” since the socio-political situation in UP had significantly changed by then. However, this raises larger questions regarding making non-fiction in a changing political landscape, where being represented for courage can become a double-edged sword, she says. “Those of us in the field are reckoning with these changing realities as we continue to tell stories about our times while living through them.”